The Dark Side of the Moon by Pink Floyd

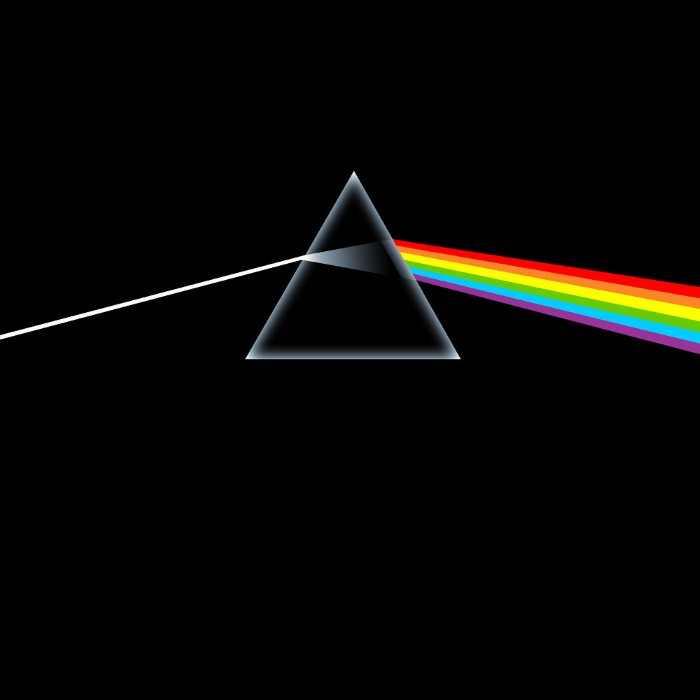

The Dark Side of the Moon is the eighth studio album by English progressive rock band Pink Floyd, released in March 1973. It built on ideas explored in the band's earlier recordings and live shows, but lacks the extended instrumental excursions that characterised their work following the departure in 1968 of founder member, principal composer and lyricist, Syd Barrett. The Dark Side of the Moon's themes include conflict, greed, the passage of time and mental illness, the latter partly inspired by Barrett's deteriorating mental state. The suite was developed during live performances and was premiered several months before studio recording began. The new material was recorded in two sessions in 1972 and 1973 at Abbey Road Studios in London. The group used some of the most advanced recording techniques of the time, including multitrack recording and tape loops. Analogue synthesisers were given prominence in several tracks, and a series of recorded interviews with the band's road crew and others provided the philosophical quotations used throughout. Engineer Alan Parsons was directly responsible for some of the most notable sonic aspects of the album, and the recruitment of non-lexical performer Clare Torry. The album's iconic sleeve features a prism that represents the band's stage lighting, the record's lyrical themes, and keyboardist Richard Wright's request for a "simple and bold" design. The Dark Side of the Moon was an immediate success, topping the Billboard Top LPs & Tapes chart for one week. It subsequently remained in the charts for 741 weeks from 1973 to 1988. With an estimated 50 million copies sold, it is Pink Floyd's most commercially successful album and one of the best-selling albums worldwide. It has twice been remastered and re-released, and has been covered in its entirety by several other acts. It spawned two singles, "Money" and "Time". In addition to its commercial success, The Dark Side of the Moon is one of Pink Floyd's most popular albums among fans and critics, and is frequently ranked as one of the greatest rock albums of all time.

<i>The Dark Side of the Moon</i> is a little like puberty: Feel how you want about it, but you’re gonna have to encounter it one way or another. Developed as a suite-like journey through the nature of human experience, the album not only set a new bar for rock music’s ambitions, but it also proved that suite-like journeys through the nature of human experience could actually make their way to the marketplace—a turn that helped reshape our understanding of what commercial music was and could be.<br /> If pop—even in the post-Beatles era—tended toward lightness and salability, <i>Dark Side</i> was dense and boldfaced; if pop was telescoped into bite sizes, <i>Dark Side</i> was shaped more like a novel or an opera, each track flowing into the next, bookended by that most nature-of-human-experience sounds, the heartbeat.<br /> Even compared to other rock albums of the time, <i>Dark Side</i> was a shift, forgoing the boozy extroversion of stuff like The Rolling Stones for something more interior, private, less fun but arguably more significant. In other words, if <i>Led Zeppelin IV</i> was something you could take out, <i>Dark Side</i> was strictly for going in. That the sound was even bigger and more dramatic than Zeppelin’s only bolstered the band’s philosophical point: What topography could be bigger and more dramatic than the human spirit?<br /> As much as the album marked a breakthrough, it was also part of a progression in which Floyd managed to join their shaggiest, most experimental phase (<i>Atom Heart Mother</i>, <i>Meddle</i>) with an emerging sense of clarity and critical edge, exploring big themes—greed (“Money”), madness (“Brain Damage”, “Eclipse”), war and societal fraction (“Us and Them”)—with a concision that made the message easy to understand no matter how far out the music got. Drummer Nick Mason later noted that it was the first time they’d felt good enough about their lyrics—written this time entirely by Roger Waters—to print them on the album sleeve.<br /> For one of the most prominent albums in rock history, <i>Dark Side</i> is interestingly light on rocking. The cool jazz of Rick Wright’s electric piano, the well-documented collages of synthesiser and spoken word, the tactility of ambient music and dub—even when the band opened up and let it rip (say, “Any Colour You Like” or the ecstatic wail of “The Great Gig in the Sky”), the emphasis was more on texture and feel than the alchemy of musicians in a room.<br /> Yes, the album set a precedent for arty, post-psychedelic voyagers like <i>OK Computer</i>-era Radiohead and Tame Impala, but it also marked a moment when rock music fused fully with electronic sound, a hybrid still vibrant more than five decades on. The journey here was ancient, but the sound was from the future.