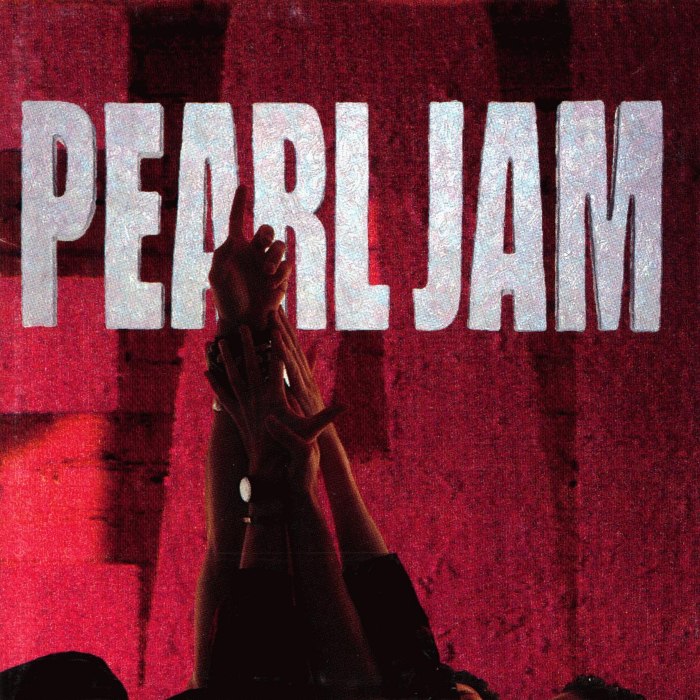

Ten by Pearl Jam

Ten is the debut studio album by the American alternative rock band Pearl Jam, released on August 27, 1991 through Epic Records. Following the disbanding of bassist Jeff Ament and guitarist Stone Gossard's previous group Mother Love Bone, the two recruited vocalist Eddie Vedder, guitarist Mike McCready, and drummer Dave Krusen to form Pearl Jam in 1990. Most of the songs began as instrumental jams, to which Vedder added lyrics about topics such as depression, homelessness, and abuse. Ten was not an immediate success, but by late 1992 it had reached number two on the Billboard 200 chart. The album produced three hit singles: "Alive", "Even Flow", and "Jeremy". While Pearl Jam was accused of jumping on the grunge bandwagon at the time, Ten was instrumental in popularizing alternative rock in the mainstream. The album has been certified diamond by the RIAA in the United States. By 2011, it had sold around 9,900,000 copies in the U.S., and remains Pearl Jam's most commercially successful album.

That Pearl Jam originally named themselves after the NBA player Mookie Blaylock makes a poetic kind of sense: Of all the bands to come out of the alternative-rock boom in the early ’90s, none felt so deeply connected to sports as they did—their focus, their fluidity, their kinetic energy and positive release. For as dark as the material on <i>Ten</i> is—portraits of homelessness (“Even Flow”) and mental illness (“Why Go”), family dysfunction (“Alive”) and teenage alienation elevated to physical violence (“Jeremy”)—the overall spirit of their 1991 debut is one of brightness and vitality, of rising above. As the story goes, singer Eddie Vedder—a gas station attendant in San Diego who’d never met his bandmates before joining them in Seattle—came up with his first round of lyrics for their demo tape while he was out surfing, his feet still covered in sand as he laid down vocals. Where decades of pop culture had split notions of male identity into macho and sensitive, jocks and nerds, Pearl Jam, in their own unwitting way, brought them together: Here were five very earnest young guys, desperate to take you above the rim.<br /> And for all the stereotypes of Seattle rock as grungy and monochromatic, <i>Ten</i> (its title a tribute to Blaylock’s jersey number) has a broad palette: syncopated hard rock (“Once”), fragile ballads (“Black”), Hendrix-indebted psychedelia (“Deep”). Where Kurt Cobain ironised conventional guitar solos by purposefully screwing his up, Mike McCready plays with the passion and enthusiasm of someone who still believes in them—a distinction that not only kept continuity with classic rock, but made Pearl Jam more akin to Guns N’ Roses and Metallica than, say, the Melvins. And while his subject matter was intimate, Vedder never sang like he belonged anywhere smaller than an arena, creating a prototype for basically every famous rock vocalist in his wake.<br /> He later worried it was all too much—too open, too personal, too vulnerable. But the lack of emotional distance is part of what makes <i>Ten</i> so distinct. Prior to Vedder joining the band, guitarist Stone Gossard and bassist Jeff Ament had played in Mother Love Bone alongside vocalist Andy Wood, who died of a drug overdose in 1990. They were looking for a new beginning; Vedder was looking for a chance. Standing onstage at the Pinkpop festival two years later, in the summer of 1992, around the time that <i>Ten</i> was certified gold, Vedder, gasping for air, turns his Polaroid camera on a crowd in the tens of thousands. He’d later tell an interviewer backstage that it was overwhelming to look out at such a sea of people—as if, in disbelief, he’d needed those pictures as proof that it had really happened. At a moment when mainstream rock was in upheaval, Pearl Jam’s real rebellion was to live.