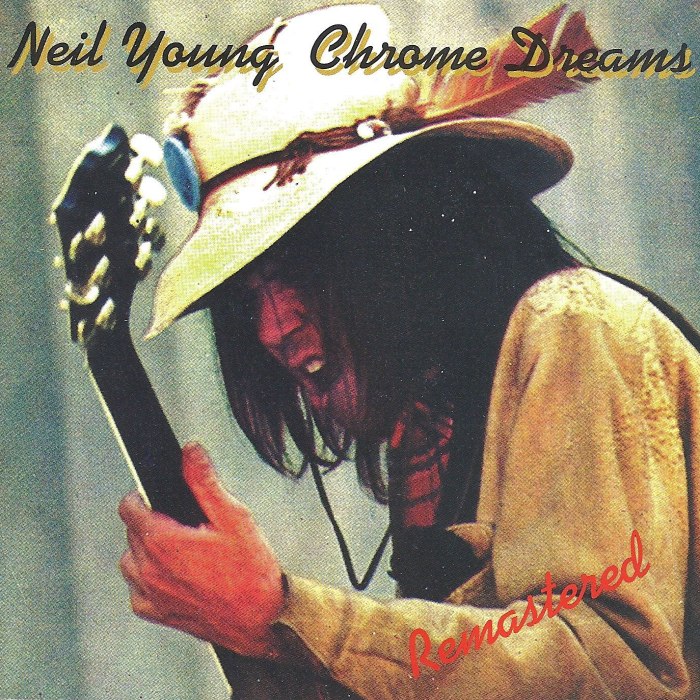

Chrome Dreams by Neil Young

Chrome Dreams is a 1977 unreleased album by Neil Young, and also an acetate from that period which is claimed to be of that album. Jimmy McDonough's Shakey: Neil Young's Biography supports the claim that Chrome Dreams is indeed a bootlegged acetate with said title. A document that accompanied the acetate (which according to Young's archivist Joel Bernstein is a forgery) gave the impression that Young had officially given Chrome Dreams as the title, inspired by rumours in the press of a new album with the same title. Young is quoted as saying "What Chrome Dreams really was, was a sketch that Briggs drew of a grille and front of a '55 Chrysler, and if you turned it on its end, it was this beautiful chick...I called it Chrome Dreams." Writing in The Guardian, Alexis Petridis opined that the album "could have been Young's strongest album of the 70s". There have been a number of unofficial recreations of Chrome Dreams. Three of the songs featured on Chrome Dreams were officially released in September 2017 on Hitchhiker. On October 23, 2007, Neil Young released a new album entitled Chrome Dreams II. Song information Chrome Dreams features a large amount of still-unreleased material. The version of "Powderfinger" included is the original acoustic demo, while the "Sedan Delivery" featured is at a slower pace than the Rust Never Sleeps take and contains an additional verse. "Pocahontas" is the same version heard on Rust Never Sleeps without overdubs. "Hold Back the Tears" is a radically different take compared to the one that appears on American Stars 'n Bars, also featuring additional lyrics. "Too Far Gone" would not see release until 1989's Freedom. It is presented on Chrome Dreams with Crazy Horse's Frank "Poncho" Sampedro accompanying Young on a 1917 mandolin. "Stringman", a piano ballad, was (according to Shakey) written for Jack Nitzsche and is presented as a performance from Young's 1976 European tour with slight studio overdubs. Eighteen years later Young revived it for his Unplugged performance, never having released the song as a studio track. "Homegrown" here is a different mix than the version on American Stars 'n Bars. The rest of the songs are for the most part identical to their releases on subsequent albums.

To hear his producer David Briggs describe it, recording with Neil Young in the mid-’70s was less like a studio session than a seance. He’d come in without a plan, stare at Briggs for 20 minutes or so and start playing: “Pocahontas”, “Powderfinger”, “Captain Kennedy”—cold peaks in the vast range of his catalogue. Like the music later released on <i>Hitchhiker</i>, a lot of the long-shelved 1977 album <i>Chrome Dreams</i> was made at Indigo Ranch in Malibu, where, according to owner-engineer Richard Kaplan, Young had a standing date on full moons. Listen in to “Will to Love”, which he started at home, and you can hear the fireplace crackling. Fans will be familiar with a lot of this stuff already, albeit in slightly different forms: A slower, hazier “Sedan Delivery” (originally from the <i>Zuma</i> sessions and punked up on <i>Rust Never Sleeps</i>), a version of “Hold Back the Tears” stripped of its Nashville zazz. Having liberated himself from Crosby, Stills & Nash (telegram to Stephen Stills after disappearing from tour: “Dear Stephen, Funny how things that start spontaneously end that way. Eat a peach, Neil”) and turned out two definitive albums with Crazy Horse (<i>Zuma</i> and <i>Tonight’s the Night</i>), he returned to the solitude implicit in his music whether accompanied or not. His dreams are American (a roundtable about the Astrodome with Marlon Brando and Pocahontas) and his passion so quietly intense you’ll consider a restraining order (“Look out for my love/It’s in your neighbourhood”—that ain’t a threat, it’s a promise). As history, <i>Chrome Dreams</i> serves as connective tissue between the haze of his early to mid-’70s and the rootsy return of <i>Comes a Time</i> and <i>Hawks & Doves</i>, not to mention affirming Young’s status as progenitor of spare, shivery indie-folk artists like Elliott Smith and early Bon Iver. And while releasing an album nearly 50 years after deciding to not release it might seem overly thorough, Young’s late-career vault-clearing feels like a part of the same unvarnished honesty that makes his music so penetrating. He didn’t promise it’d all be great, he once said—only that it’d be what it was.