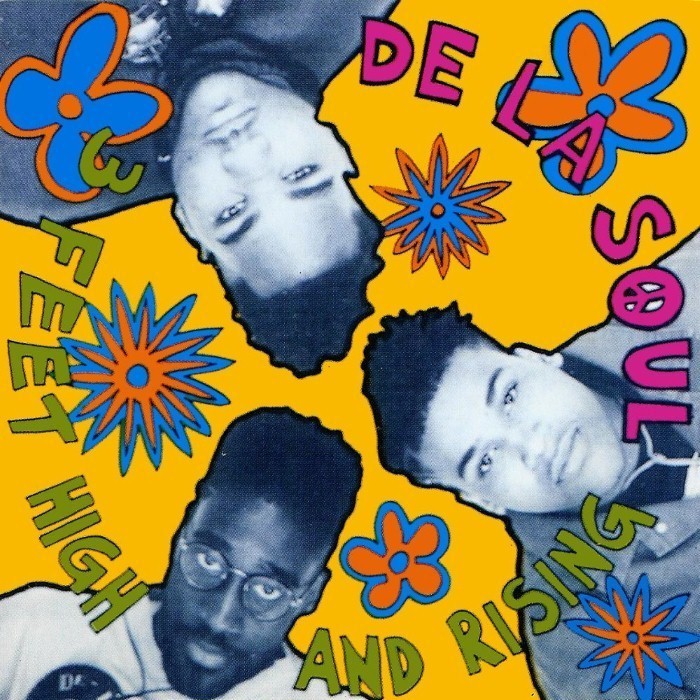

3 Feet High and Rising by De La Soul

3 Feet High and Rising is the debut album from American hip hop trio De La Soul, released in 1989. The album marked the first of three full-length collaborations with producer Prince Paul, which would become the critical and commercial peak of both parties. It is consistently placed on 'greatest albums' lists by noted music critics and publications. Robert Christgau called the record "unlike any rap album you or anybody else has ever heard." In 1998, the album was selected as one of The Source Magazine's 100 Best Rap Albums.. A critical, as well as commercial success, the album contains the well known singles, "Me Myself and I", "The Magic Number", "Buddy", and "Eye Know". On October 23, 2001, the album was re-issued along with an extra disc of B-side tracks, and alternative versions. The album's title was inspired by a line in the Johnny Cash song "Five Feet High and Rising." The album is discussed in detail by De La Soul in Brian Coleman's book Check the Technique. It was selected by the Library of Congress as a 2010 addition to the National Recording Registry, which selects recordings annually that are "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".

<b>100 Best Albums</b> “We was just three spaced kids who felt like we was doing something special,” Trugoy the Dove (Dave Jolicoeur), one-third of pioneering Long Island rap trio De La Soul, told Apple Music in 2018. “It felt good to stand out, but we were immersed in what hip-hop was at that time—the culture, the music, everything.” The fact that Trugoy passed away in February 2023, mere weeks before De La Soul’s catalogue finally became available on streaming, dampened what should have been a celebration decades in the making. Transmitting live from Mars—or, more specifically, the Long Island suburbs—De La Soul emerged fully formed and casually bugged-out in 1988 with “Plug Tunin’”, a 12-inch of “naughty noise” that mixed off-the-wall wordplay (“Answering any other service/Prerogative praised positively I’m acquitted”) with a kitschy arsenal of the most off-kilter samples hip-hop has ever seen. On their subsequent debut album, 1989’s <i>3 Feet High and Rising</i>, the group—Trugoy, Posdnuos (Kelvin Mercer) and DJ P.A. Pasemaster Mase (Vincent Mason)—and deliriously twisted producer Prince Paul laid out a 63-minute blueprint for rap’s odd future, a playful, quirky masterwork that popped the balloon of hip-hop formalism. They were outcasts before Outkast, the roots of The Roots, the big brothers to Little Brother. De La were alternative-nation thought-leaders doing for hip-hop what contemporary weirdos like Jane’s Addiction, Sonic Youth and the Pixies were doing for rock. What started as a trio of rap misfits making leftfield funk ultimately evolved into the most consistently great catalogue in New York hip-hop history. Afrika Bambaataa famously combed the corners of Planet Rock looking for the perfect beat, but De La’s genre-agnostic outlook to crate-digging imbued hip-hop with alien moods and new textures. Their tools weren’t just blips of James Brown and Funkadelic (though the latter’s rubbery melody would drive “Me Myself and I”, the band’s lone moment in the Top 40). De La Soul and Prince Paul’s playground included <i>Schoolhouse Rock!</i>, Steely Dan, learn-to-speak-French records, the Parliament song with the yodelling, Eddie Murphy, Johnny Cash, a Liberace cassette they found in the studio, loads of ’60s soul and psychedelia-adjacent rock groups like The Turtles. (The latter group sued the trio that year, the first major sampling lawsuit, a historic moment for a historic album. The necessary work to clear all the samples from a career of creative copyright infringement helped keep the bulk of De La Soul’s catalogue off streaming services for years.) “Everything we did on <i>3 Feet High and Rising</i> was based off ideas we had been putting together since we were 15, 16,” said Posdnuos. Lighthearted skits and interludes filled the album with wacky accents, inside jokes (“What does, ‘Tuhs eht lleh pu’ mean?”) and whispered silliness. “Stand by Me” is looped for a 56-second song about body odour. Loopy slang words (either invented or inherited from fellow members of the Native Tongues crew) create an insular universe where sex songs are about “buddy” and “jenny”, something good is “strictly Dan Stuckie” and your MCs for the evening are “Plug One” and “Plug Two”. Their freewheeling poetry—what they called a “Change in Speak”—broke sentences apart into expressionist clouds that ranged from pure poetry to inspired nonsense: “When that negative number fills up the cavity/Maybe you can subtract it/You can call it your lucky partner/Maybe you can call it your adjective.” Proudly eccentric and preaching their message of self-expression while dressed in African medallions instead of fat gold ropes, they became the bohemian model for years of alternative-minded rappers. “We was trying to take it to the next place, letting people know there’s individuality here,” Trugoy said. “Not all of us have to wear Adidas; you could wear Le Coq Sportif. There’s so many other things we could do.” You can hear, and see, their influence in the spiritual verses of Arrested Development and P.M. Dawn, underground lyricists like Common and Mos Def, and even pop polyglots like Gorillaz, Black Eyed Peas and Beck.